Outcome of COVID-19 in Pregnancy and the Harms of Lockdowns

A study published in August 2022 from South Korea provided good news about Covid-19 in pregnancy. Outcomes for South Korean pregnant women are the same as non-pregnant women in the reproductive age of 15 to 45 years.

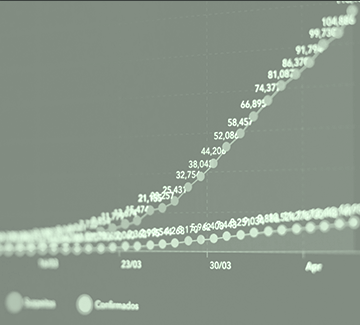

This was the first population wide study of the effect of COVID-19 in pregnancy. It used data from the Korean National Health Insurance. They studied 12.4 million women aged 15 to 49. The following diagram shows the number of non-pregnant and pregnant women who had a positive PCR COVID-19 test and those who were hospitalised with severe COVID-19 between November 2019 and July 2021.

In South Korea COVID-19 infection is defined as a positive PCR test irrespective of clinical symptoms. Government documents show severe disease was diagnosed as temperature over 38.0℃ with fever reducing medicine, shortness of breath/difficulty breathing or diagnosed with pneumonia after a CT scan.

Was COVID-19 in Pregnancy in South Korean Women Associated With Worse Outcomes Than For Non-Pregnant Peers? A Summary of the Findings

- Pregnant women were LESS likely to have a positive test for COVID-19 (0.11% pregnant women (n= 705) compared to 0.49% of non pregnant women (n = 57,323)).

- There was no significant difference in the percentage of women who had severe disease (7.8% of pregnant women compared to 10% of non-pregnant women).

- Pregnant women with a positive test for COVID-19 had more miscarriages (13.3% verses 9.2%).

- Pregnant women with a positive test for COVID-19 were LESS likely to have pregnancy complications than pregnant women without COVID-19. AND specifically they had fewer preterm births and fewer caesarean section deliveries.

- Babies born to women with a positive test for COVID-19 were more likely to go to the Neonatal Intensive care unit (18.7% verses 7.7%) but were not more likely to suffer any serious condition or complication.

During this time Korea had an aggressive policy of testing, contact tracing and early treatment. South Korea did not institute lockdowns but contacts, cases and new arrivals in the country were required to isolate for 14 days. Treatment for COVID-19 was free. Lopinavir/ritonavir and hydroxychloroquine were the most commonly used antivirals for COVID-19 in South Korea. Note that hydroxycholorquine is disallowed in New Zealand for the treatment of Covid.

How Does This Compare to Outcomes of COVID-19 in Pregnancy in the United Kingdom?

The UK has population level data on the outcome of pregnant women admitted to hospital with COVID-19 via its national Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) to which all 194 UK hospitals submit data on pregnancy complications. Researchers have used this accumulating data to publish three reports on the outcome of COVID-19 in pregnancy in June 2020 (427 women), March 2022 (1148 women) and April 2022 (4436 women).

Here is a summary of the findings.

- Routine PCR testing was introduced at the end of May 2020.

- 50% of women routinely screened were asymptomatic and were excluded from analysis. This left 4436 women who had a postive PCR test and COVID-19 type symptoms.

- Only half of the women with a positive PCR and COVID-19 symptoms were admitted for COVID-19 concerns. The remainder were admitted for labour and birth or for other obstetric reasons.

- Women were asked if they had symptoms consistent with COVID-19 within 2 weeks of admission (cough, fever, sore throat, headache, fatigue, breathlessness, limb or joint pain, runny nose, vomiting, diarrhoea, loss of smell or pneumonia on chest X-Ray). Any one who has ever been pregnant or lived with a pregnant woman will note a considerable cross over between pregnancy symptoms and COVID-19 symptoms. This was acknowledged by the authors; ‘…..most symptoms of SARS– CoV-2 are non-specific and therefore the possibility of an alternative cause of these symptoms cannot be excluded’.

- 65% had mild symptoms, 21% had moderate symptoms and 14% had severe symptoms (compare this with 7.8% in the South Korean study).

- Those most at risk were ≥30 years old, overweight, of mixed ethnicity or had gestational diabetes.

- 12% (529) were admitted to ICU, of whom 213 (40%) were ventilated.

- The proportion of women who received any drug treatment for covid-19 was small: 11.0% received antivirals, 9.8% received tocilizumab, 28.4% received maternal steroids, and 0.4% received monoclonal antibodies.

- Women in the severe group were more likely to have early delivery by caesarean section, preterm babies and stillbirths.

- Transmission of COVID-19 to newborns was uncommon.

- Hospitalization with a positive PCR test for COVID-19 was associated with increased risk of caesarean section, irrespective of symptom status. The authors said this was clear evidence of the indirect impact of COVID-19 on maternity care. They suggested that as the pandemic continues and possibly an endemic state is reached there needs to be an awareness of the need to prevent complications such as neonatal prematurity and long-term complications associated with over-intervention in care.

COVID vaccination status was collected in only 1761 women, of whom only 54 (3%) had one or two doses. Six of the vaccinated women (11.1%) had severe disease. This is the only data presented in the three publications about COVID-19 vaccinations. The authors stated that the data showed that vaccination prevented admission and demonstrated ‘promising vaccine efficiency’. This is a little perplexing as the overall admission to ICU rate was 12%.

During the period of this study there were three waves of COVID-19 variants. The proportion of women with moderate and severe Covid-19 in pregnancy increased with each variant 25% to 36% and 43% in the wild-type, alpha variant, and delta variant respectively. This was in line with the increased severity of COVID-19 disease seen in the general population.

Outcomes of COVID-19 in pregnancy were compatible with outcomes of non-pregnant women of reproductive age during the wild variant of COVID-19. No comment on this comparison for alpha and delta variants was provided.

The proportion of women receiving drug treatment for COVID-19 management was low in each time period, wild-type 10.4%, alpha 14.9% and delta 13.6%.

The UK data does not include the outcome of non-pregnant women in the reproductive age range with COVID-19 so unlike the South Korean study, no comparison of outcomes is possible.

A number of women died from COVID-19 in pregnancy and we will look at their stories next.

Review of Maternal Deaths Associated With COVID-19 in Pregnancy

The UK has a group whose acronym is MBRRACE which provides reports on women who die during or just after pregnancy (maternal deaths). Their reports usually cover 3 years of data. However, they released two Rapid Reports on maternal deaths due to COVID-19, one in 2020 which covered 16 deaths in March to 14 April 2020, and the other in July 2021 which covered 17 maternal deaths due to COVID-19 from June 202 to March 2021.

The first report was of 10 maternal deaths in women who had a positive test for COVID-19 and 6 other maternal deaths in women without COVID-19 but their deaths were related to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. In two cases death was due to excessive blood loss despite exemplary management and were not related to COVID-19. Of the remaining 8 women where death was caused by COVID-19 none were treated with antivirals.

- Two died in hospital after their presenting symptoms of severe disease were not recognised and their deterioration was poorly managed in hospital.

- Two died of thromboembolism after delivery and had not received prophylactic anticoagulation despite multiple risk factors.

- Three women died at home or presented late because of fear of coming to hospital or being advised by telephone to stay home.

- One woman only was judged to have died despite good care.

In the same time period six other maternal deaths occurred in women who did not have COVID-19 but whose care was compromised by pandemic restrictions.

- Four women committed suicide as pandemic changes to service provision meant they could not access appropriate face to face mental health care.

- Two women died as a result of domestic violence during lockdown. One woman reported an attempted murder by her partner and was told to stay home and lock the doors. She was murdered the following day.

MBRRACE Rapid Report on Maternal Deaths Associated With COVID-19 in Pregnancy Between June 2020 and March 2021, Published in July 2021

Seventeen women died during pregnancy or in the 6 weeks after delivery.

Of these women 14 died after a positive COVID-19 test or were found to have COVID-19 at postmortem. The reviewers found ten of these women died due to COVID-19 infection which gave a mortality rate of 1.7/100,000 pregnancies. When each case was reviewed they found that only one woman received good care, in two cases care could have been better but probably would not have changed the outcome. In 7 of the 10 women better care could have changed the outcome.

- Three women who had positive COVID-19 PCR tests died of obstetric-related conditions; two women died in hospital without proper treatment as their COVID-19 positive status was thought be responsible for their presenting symptoms. Another woman died at home of a pulmonary embolism while she waited for a telephone GP appointment after she submitted an on-line request due to a painful swollen leg.

- Two who died in hospital of COVID-19 were not treated according to obstetric guidelines for pregnant women with COVID-19.

- Two women with cough died of COVID-19 after a GP practice telephone consultation failed to appreciate how unwell they were. One died at home and the other was admitted 3 days later with oxygen saturations of 60%.

- Two women delayed seeking care for a cough, one died at home and one died after a very late presentation to hospital.

The remaining three of the 17 women did not have COVID-19 but their deaths were influenced by pandemic restrictions.

- Two died at home of overwhelming infection after only being able to access only telephone consultations so no physical examination was possible.

- One died after an unattended home delivery because she was too fearful of catching COVID-19 in hospital.

In summary, if we look at all 33 deaths reported we find that 25 deaths were associated with pandemic restrictions and lack of face to face care, fear instilled by media and government messaging and COVID-19 fixation on behalf of hospital staff.

- In 11 cases pandemic restrictions and lack of access to face to face consultations resulted in wrong diagnoses, delayed diagnosis or death by suicide or family violence.

- In six cases fear of COVID-19 prevented or delayed women seeking help.

- In eight cases wrong treatment was given in hospital. In 6 cases this was due to COVID-19 status of pregnant women.

The reviewers called this ‘COVID-19 fixation’.

The stories of these women are incredibly sad. They show us that the strategies used to manage COVID-19 disease irreparably affected the outcome for most of these women. It is clear that COVID-19 disease can be serious and indeed fatal for women with risk factors, the same risk factors for any severe infectious disease in pregnancy. However, more women have died from factors associated with the population-wide COVID-19 management strategy than from COVID-19 disease itself.

The wide-ranging, serious consequences of the lockdown strategy in the UK is now being discussed.

COVID-19 Fixation Continues

In November 2021 a different group of researchers used data from the National Health Service (NHS) Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) to look at the outcomes of Covid-19 in pregnancy as defined by a positive PCR test at the time of admission to hospital. They concluded that:

SARS-CoV-2 infection at the time of birth is associated with higher rates of fetal death, preterm birth, preeclampsia, and emergency cesarean delivery. There were no additional adverse neonatal outcomes, other than those related to preterm delivery.

Having read so far into this article can you think of reasons why the approach used in this study could at best be described as simplistic and at worst misleading? You can find out more about the use of a PCR test to diagnose a disease state here.

The authors of the MBRRACE reports wrote a letter to the Editor of the journal in which the above study was published in November 2021. The title and sections of letter are reproduced here.

Misclassification, Bias and Unnecessary Anxiety

We read with concern the article by Gurol-Urganci et al purporting to show an increase in stillbirths and preeclampsia among women who received a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 at the time of birth admission in England. This association may be explained entirely by the admission SARS-CoV-2 screening policy and associated misclassification bias, rather than by a causal impact of SARS-CoV-2.

Evidence suggests that indirect impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on pregnant women, such as those caused by delayed presentation and mental health problems, are far greater than the direct impacts of COVID-19 itself. It is therefore imperative that extra care is taken to design and interpret epidemiologic studies, avoiding biases that lead to spurious findings that may cause unwarranted distress.

Studies such as this can only be undertaken on a population basis, either in populations of pregnant women in whom regular, asymptomatic screening programs are conducted both at home and in hospital settings, or, in the absence of routine, regular population screening, by conducting a comparison between population antepartum stillbirth and preeclampsia rates comparing the time periods of when the virus is circulating and when it is not. Rigorous study designs must be employed to avoid causing additional unnecessary anxieties to pregnant women and their families.

There are so many more things that could (and should) be said. But perhaps the best summary is this.

Further information about Covid-19 in pregnancy is available at COVID-19: The Unraveling of Experimental Medicine and The Golden Rule of Pregnancy.